In the United States, the average wholesale price is a prescription drug term referring to the average price for medications offered at the wholesale level. The metric was originally intended to convey real pricing information to third-party payers, including government prescription drug programs. Commercial publishers of drug pricing data such as Red Book have published AWP data since at least 1970. The pricing information is "based on data obtained from manufacturers, distributors, and other suppliers." However, despite the data source, published AWPs are generally inflated by 20% relative to actual market prices or wholesale acquisition cost for prescription drugs.

Background Pricing drugs in the California Workers' Compensation System has become more difficult as there are increasingly fewer drugs listed in the Medi-Cal primary fee schedule, which is used as the source for CAWCS drug prices. This presents a challenge of providing timely and accurate CAWCS reimbursement. Methods We evaluated physician-dispensed drugs at the transaction level, reimbursed in the CAWCS. Frequency, reimbursement rate, and total and average paid costs were reported. We matched each claim line in the CAWCS to the corresponding unit price of an alternative price benchmark including average wholesale price, wholesale acquisition cost, direct prices, national average drug acquisition cost, and Federal Upper Limit. Results Average wholesale price provided prices for 99.9% of physician-dispensed drug claims, while Medi-Cal, the current primary physician-dispensed drug benchmark provided prices for a lower percentage (92.7%) of claims.

The CAWCS prices were equivalent to 49% of the average wholesale price, 95.5% of Medi-Cal, 126.7% of the wholesale acquisition cost, 266% of the Federal Upper Limit, 64.4% of direct prices, and 197% of national average drug acquisition cost-estimated prices. Conclusions The CAWCS current Medi-Cal pricing for physician-dispensed drugs is better than all alternatives in terms of price availability, transparency, and budget neutrality, but pricing availability may decrease over time as Medi-Cal moves to managed care. National average drug acquisition cost is the next best alternative, but it requires combinations of pricing benchmarks to maximize its price availability. Prescription drug pricing has moved center stage in a health care industry that is becoming more and more complex. With the inclusion of new groups of stakeholders, more varied incentive systems, greater competition, and more complicated benefit structures, the "true" cost of prescription drugs has grown increasingly elusive.

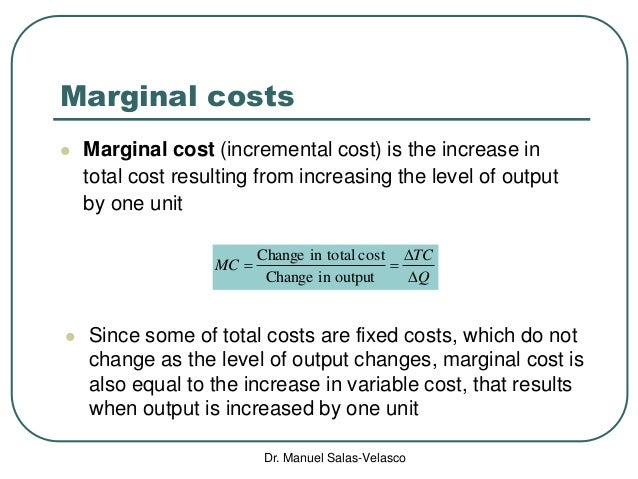

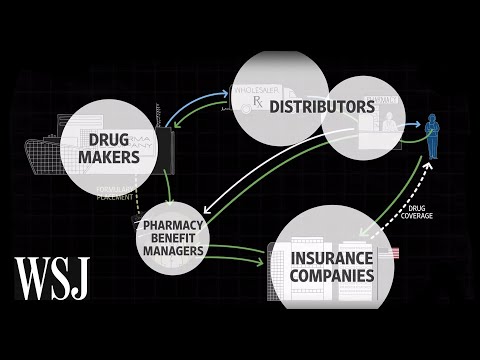

Drug prices are subject to various types of discounts and rebates, seen and unseen, on both the public and private side. Each drug sold by a manufacturer, therefore, is subject to multiple prices, and little is known publicly about this pricing information. In addition, the issue of drug pricing has implications for other payment systems, such as the Medicare resource-based relative value scale for physician reimbursement and the state Medicaid reimbursement formulas for prescription drugs.

In certain instances where providers or pharmacies believe they are inadequately compensated for administering or dispensing prescription drugs, an inflated average wholesale price is relied upon to make up the difference. From a policy perspective, therefore, the AWP is part of a larger pricing infrastructure that requires examination. The continued debate about the establishment of a comprehensive Medicare prescription drug benefit has only intensified policymakers' focus on drug prices.

There is a lack of a uniform proxy for defining direct medical costs in the US. This potentially important source of variation in modelling and other types of economic studies is often overlooked. The extent to which increased expenditures for an intervention can be offset by reductions in subsequent service costs can be directly related to the choice of cost definitions. To demonstrate how different cost definitions for direct medical costs can impact results and interpretations of a cost-effectiveness analysis. The IMS-CORE Diabetes Model was used to project the lifetime (35-year) cost effectiveness in the US of one pharmacological intervention 'medication A' compared with a second 'medication B' for type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The complications modelled included cardiovascular disease, renal disease, eye disease and neuropathy. Complication costs were obtained from a retrospective database study that extracted anonymous patient-level data from adjudicated medical and pharmaceutical claims. Costs for pharmacy services, outpatient services and inpatient hospitalizations were included. Cost definitions for complications included charged, allowed and paid amounts, and for medications included both wholesale acquisition cost and average wholesale price . The cost-effectiveness results differed according to the particular combination of cost definitions employed.

When the analysis incorporated WAC medication prices with charged amounts for complication costs, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for medication A versus medication B was $US6337 per QALY. When AWP prices were used with charged amounts, medication A became a dominant treatment strategy, i.e. lower costs with greater effectiveness than medication B. For both allowed and paid scenarios, there was a difference in the ICER of over $US10,300 per QALY when medication prices were defined by WAC versus AWP. Ratios of medication costs to cardiovascular complication costs ranged from under 0.45 to over 1.7, depending upon the combination of costing definitions. Explicitly addressing the cost-definition issue can help provide meaningful cost-effectiveness data to payers for policy development and management of healthcare expenditures.

It can also help move the pharmacoeconomics and outcomes research fields forward in terms of both methodology and practical application. Federal Medicaid law does not dictate the amount that a state may pay for the drug itself. For brand-name drugs or for generic drugs with fewer than three generic versions the reimbursement is the lower of the pharmacist's usual and customary charge to the general public and the drug's estimated acquisition cost.17 The EAC is a state's estimate of the price generally paid by providers for the drug. Most states pay for drugs at a percentage discount below a drug's published AWP.18 Information compiled by the National Pharmaceutical Council indicates that the reimbursement formulas for state Medicaid agencies range from AWP minus 4 percent in Wyoming to AWP minus 15.1 percent in Michigan.

(See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the state Medicaid reimbursement formulas.) The average is 10.31 percent below AWP, according to the DHHS Office of Inspector General . The core of the plaintiffs' claim is that the published AWPs for the drugs at issue did not reflect the discounts and rebates that the drug manufacturers offered to physician providers. The plaintiffs further alleged that the defendant pharmaceutical companies then "marketed the spread"-that is, advertised the potential windfall to providers-in an attempt to increase the market share of their drugs over the competition. Motivating the plaintiffs' complaints, of course, is the fact that an increase to the AWPs directly resulted in an increase to the payments the plaintiffs were required to make in the form of reimbursement, insurance, or coinsurance. According to the district court's "representative" examples, markups to AWPs were significant and unpredictable, ranging from 27.0% to 1131.7%, depending on the drug and the year. A recent report indicated that the drug industry's published wholesale prices, which serve as the basis for Medicare payments to providers, are significantly higher than the providers' actual acquisition costs.

Physicians are able to obtain Medicare-covered drugs at prices significantly below current Medicare payments. (See Figure 1 for an example of this pricing structure.) In certain instances, drug manufacturers may make even deeper discounts available to providers, in exchange for the providers' willingness to prescribe their drugs over those of their competitors. The result is a wide range of unknown prices being paid for prescription drugs by providers, who are then reimbursed a fixed amount by Medicare, leading to widely varying profit margins for different doctors.

The AWP has often been equated with a "sticker price" or "list price," as those terms are used in the automobile industry. It has become an important prescription drug pricing benchmark for payers throughout the health care industry. Despite its name, however, the AWP is not an accurate reflection of actual market prices for drugs.

As noted, it is a price derived from self-reported manufacturer data for both branded and generic drugs. There are no requirements or conventions that the AWP reflect the price of any actual sale of drugs by a manufacturer, or that it be updated at established intervals. It is not defined in law or regulation, and it fails to account for the deep discounts available to various payers, including certain federal agencies, providers, and large purchasers, such as HMOs. The evidence supported a finding that AstraZeneca unfairly and deceptively published an artificial average wholesale price for Zoladex that gave no indication of the actual, substantial discounts and rebates it was providing in the market.

This conduct by the appellant was contrary to Congress's intent in designing the Medicare program, and it clearly transgressed the expectations of the marketplace. That AstraZeneca also used the scheme to attempt to induce physicians, who stood to profit from the difference between their acquisition cost and the AWP-based reimbursement cost, to prescribe the drug to make a profit rather than based on therapeutic concerns underscores the serious nature of the company's conduct. This is precisely the kind of scheme that Chapter 93A was meant to address, and its use to impose liability here is consistent with the Constitution, with federal and state law, and with the goals, purposes, and design of the Medicare program. Reimbursement options for pharmaceuticals reimbursed under Medicare Part B (physician-dispensed drugs) are changing and the new comprehensive Part D Medicare outpatient drug benefit brings further changes. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of replaces traditional policy, of reimbursing Part B drugs at 95% of average wholesale price , with a percentage markup over the manufacturer's average selling price; in 2005 an indirect competitive procurement option will be introduced.

In our view, although AWP-based reimbursement has been fraught with problems in the past, these could be fixed by constraining growth in AWP and periodically adjusting the discount off AWP. With these revisions, an AWP-based rule would preserve incentives for competitive discounting and deliver savings to Medicare. By contrast, basing Medicare reimbursement on a manufacturer's average selling price undermines incentives for discounting and, like any cost-based reimbursement rule, may result in higher prices to both public and private purchasers. Indirect competitive procurement for drugs alone, using specialty pharmacies, pharmacy benefit managers, or prescription drug plans, is unlikely to constrain costs to acceptable levels unless contractors retain flexibility to use standard benefit management tools. Folding Part B and Part D into comprehensive contracting with health plans for full health services is likely to offer the most efficient approach to managing the drug benefit.

Average wholesale price is a term which is generally used with prescription drugs. AWP refers to the average value at which wholesalers sell drugs to physicians, pharmacies, and other customers. AWP is the generally accepted standard measure for calculating the cost of a particular medication. It has become an important prescription drug pricing benchmark for prescription drug pricing and reimbursement throughout the health care industry. AWP is generally 20% greater than the value for which a manufacturer sells their products to distributors and large customers. The reimbursement rates between PBMs and pharmacies are based on different pricing benchmarks and depend on the drug type and the pharmacy's degree of market power.

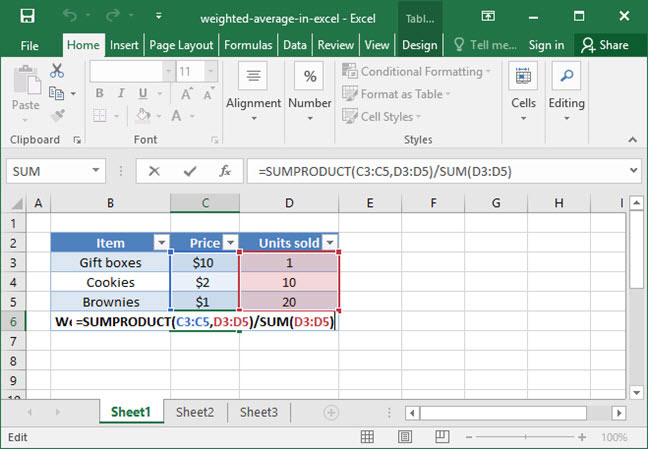

Manufacturers set a drug's list price and sell drugs to wholesalers at the wholesale acquisition cost . Another benchmark, the average wholesale price , is typically calculated to be 20 percent higher than the WAC. Wholesalers — there are three in the U.S., AmeriSource Bergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson — pass through the price with a small markup and distribute the drug to pharmacies, which are then reimbursed by public and private payers. Retail pharmacies derive 80 percent of their revenue from private insurers and 15 percent of their revenue from Medicaid.25 Private insurers base reimbursement to pharmacies on the AWP, minus a discount. We then present a theoretical framework for the pricing of branded pharmaceuticals, without and then in the presence of prescription drug insurance, noting factors affecting the relative impacts of drug insurance on prices and on utilization.

With this as background, we summarize major long-term trends in copayments and coinsurance rates for retail and mail order purchases, average percentage discounts off Average Whole Price paid by third party payers to pharmacy benefit managers as well as average dispensing fees, and generic penetration rates. To compare methods of prescription reimbursement in Japan and the United States. Data were obtained through interviews and a search of the pharmacy literature using MEDLINE, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, the Iowa Drug Information Service, and the Internet.

Search terms were pharmacy, dispensing fee, reimbursement, prescriptions, Japan, United States, and average wholesale price . The reimbursement systems for prescriptions differ widely between Japan and the United States. The reimbursement system in the United States is fairly straightforward and easy to understand; it is generally based on product cost (e.g., AWP minus a percentage) plus a small dispensing fee. Reimbursement formulae have four components, including fees for professional dispensing, drug cost, counseling and administration, and medication supplies and devices.

Additionally, various adjustments to the final amount are made based on dosage form, length of therapy, number of prescriptions dispensed by the pharmacy per month, and when the prescription is filled (e.g., after hours, on Sundays or holidays). In Japan, each pharmacist is limited to filling 40 prescriptions per day, but each "prescription" can involve several medication orders, making it difficult to compare Japanese pharmacists' workloads with those of their counterparts in the United States. In addition, Japanese pharmacists are provided remuneration for providing various cognitive services, such as taking a patient history, counseling a patient, consulting with a physician, and identifying drug-related problems. Japan and the United States have very different methods of reimbursing pharmacists for dispensing prescriptions, each with positive and negative features. After leaving community pharmacy to pursue a career in the pharmaceutical industry, my father's questions about prescription drug pricing continued, but the questions now included why prescription prices seemed to increase as they did, and how manufacturers determined the prices they charged to their customers. During the mid-1980s, other civil servants and federal employees— more specifically, members of Congress and Senators—began asking similar questions.

They also wanted to know why manufacturers were often willing to offer such steep discounts to the US Department of Veterans Affairs on the Federal Supply Schedule and through VA depots, while Medicaid was paying among the highest prices. After all, they reasoned, the federal government is the largest volume purchaser of prescription drugs, so it should get the lowest price—or at least a price as low as the manufacturers' best price offered to other customers. The frequency and magnitude of price increases levied by manufacturers also did not go unnoticed by Congress. As if to provide the answers to these questions, Congress incorporated the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program into the budget to become effective January 1991. For new drugs or new formulations of existing drugs, if drug price information is unavailable pursuant to clause of subparagraph , drug manufacturers and wholesalers shall submit drug price information to the department or a vendor designated by the department for the purposes of establishing the actual acquisition cost. Drug price information shall include, but not be limited to, net unit sales of a drug product sold to retail pharmacies in California divided by the total number of units of the drug sold by the manufacturer or wholesaler in a specified period of time determined by the department.

Business owners set prices for the goods and services they provide based on a variety of factors. For a business to be profitable, revenue from the pricing of all goods and services should be greater than the sum of all costs of the business. In the case of pharmacies, pricing of medications for insured patients is determined by contracts with each PBM and the government. The consolidation of the pharmacy industry may offer convenience for patients through features such as 24-hour availability or the option of picking up from alternate locations.8 Furthermore, chain or mass retail pharmacies may reduce prescription drug costs by leveraging their buying power to negotiate lower prices.

For example, chain pharmacies may purchase their drugs directly from manufacturers, bypassing the wholesaler markup in the distribution chain. These lower pharmacy acquisition prices have the potential to reduce costs for the health care system through lower generic reimbursement under MAC and GER schedules, which should then be passed on to plan sponsors and, ultimately, patients. So, with AWP and WAC both excluded from consideration, a new pricing metric descriptor was necessary to determine the Medicaid rebate, and that price became AMP. The paraphrased definition of AMP in the original version of the statute is "the average price paid to the manufacturer for the drug in the States by wholesalers for drugs distributed to the retail pharmacy class of trade .

Federal Supply Schedule prices are not included in the calculation of AMP." This relatively simple and seemingly straightforward definition of AMP would soon be complicated by the fact that the term "retail pharmacy class of trade" was not defined in the statute or in the manufacturers' Rebate Agreement. The customary prompt pay allowance typically provided to wholesalers and other direct customers was also factored into the calculation, along with any discounts to retail pharmacies . Although patient out-of-pocket costs for drugs vary greatly, patients paid a median of 53% more for these drugs in 2016 than they did in 2010, after adjusting for general inflation. During the same period, median household income rose 8.6%,22 so these out-of-pockets costs have increased relative to income.

Because we used claims to determine out-of-pocket costs, this finding persists despite coupons and patient assistance programs aimed at lowering patient spending. To fully understand Medicaid reimbursement for prescription drugs, it is important to understand the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program and the pricing mechanisms on which it is based. In response to concern about the increasing cost of prescription drugs for Medicaid beneficiaries, the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program was implemented as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. This program requires drug manufacturers to sign a rebate agreement with the federal government in order to receive payment for outpatient prescription drugs provided to Medicaid beneficiaries. The AWP, or average wholesale price, of prescription drugs was intended to represent the average price at which wholesalers sell drugs to physicians, pharmacies, and other customers.

In practice, it is a figure reported by commercial publishers of drug pricing data, such as First DataBank and Thomson Medical Economics. According to the Red Book, published by Thomson Medical Economics, the pricing information is "based on data obtained from manufacturers, distributors, and other suppliers."2 This pricing information is then sold to government entities, private insurance companies, and other purchasers of prescription drugs. U.S. spending on prescription drugs was $323 billion in 2016, up from $216 billion just 10 years ago, according to the latest government data. Pharmaceuticals' share of total healthcare expenses is also growing rapidly. As pharmacies are seemingly being built on every corner, and inside every grocery and department store, the casual observer might assume that retail pharmacies are profiting from this increase in spending on prescriptions.

But, as every pharmacy owner knows, the profit margin on prescription drug sales is slim, and it continues to narrow due to low reimbursement rates set by private and government third-party payers. The AWP does not reflect the acquisition cost for generic drugs.48PBMs pay pharmacies a negotiated MAC that is proprietary and is also not known to states. The difference between the AWP-based payment and the MAC is referred to as the "spread," or profit of the PBM. Because the components of the spread are often unknown, many states do not know how much profit PBMs retain. In 2003 the federal-state Medicaid program provided prescription drug coverage to more than 50 million people. To determine the price that it will pay for each drug, Medicaid uses the average private sector price.

When Medicaid is a large part of the demand for a drug, this creates an incentive for its maker to increase prices for other health care consumers. Using drug utilization and expenditure data for the top 200 drugs in 1997 and in 2002, we investigate the relationship between the Medicaid market share and the average price of a prescription. Our estimates imply that a 10-percentage-point increase in the MMS is associated with a 7 to 10 percent increase in the average price of a prescription.

In addition, the Medicaid rules increase a firm's incentive to introduce new versions of a drug in order to raise price. We find empirical evidence that firms producing newer drugs with larger sales to Medicaid are more likely to introduce new versions. Taken together, our findings suggest that government procurement rules can alter equilibrium price and product proliferation in the private sector.

Introduction California's Workers' Compensation System Department of Industrial Relations questioned the adequacy of the current Medi-Cal fee-schedule pricing and requested analysis of alternatives that maximize price availability and maintain budget neutrality. Objectives To compare CAWCS pharmacy-dispensed drug prices under alternative fee schedules, and identify combinations of alternative benchmarks that have prices available for the largest percentage of PD drugs and that best reach budget neutrality. Methods Claims transaction-level data (2011–2013) from CAWCS were used to estimate total annual PD pharmaceutical payments. Medi-Cal pricing data was from the Workman's Compensation Insurance System . Average Wholesale Prices , Wholesale Acquisition Costs , Direct Prices , Federal Upper Limit prices, and National Average Drug Acquisition Costs were from Medi-Span.